C H A P T E R

C H A P T E R

T E N

v

DURING THE SPRING SEMESTER OF 1974 at Saint Clare’s College in Rhodes, Ohio, Cedric Fitzgerald was the most popular thing around. He was editing the poetry magazine and the literary magazine. He had been reviewed in Black Who’s Who in American Colleges, and gone from starring in school productions to directing them. This spring, right after Easter, he was directing the first one he’d written. Any professor he had would be willing to write him a letter of recommendation for graduate school—which should have made him feel good.

They loved him at Mc Cleiss.

Now people of Saint Clare’s were of two minds about McCleiss University.

McCleiss was the large Catholic university on the other side of Rhodes with its rich kids, and the large new seminary sprawled out overlooking Lake Erie. McCleiss students never came from the lower economic ranks like Saint Clare’s kids. Or if they did they didn’t show it. McCleiss kids were not townies- which Saint Clare’s kids were suspected of being. In fact, Mc Cleiss kids were not kids. They were students, and they were academes. They went to a university which meant that in the sixties Saint Clare kids had looked on with envy while their Catholic brethren down the street had gotten to stretch out on that street and protest. Some of the priests had even come out in their cassocks to protest with them.

And being a University also meant they had more programs. McCleiss was highly selective unlike Saint Clare’s which took anybody. If you wanted to get into the really good engineering program, or biology department, you’d better transfer to McCleiss, and if you wanted any sort of graduate program, well then Saint Clare’s was definitely out.

So McCleiss, invisible from the east end of town where Saint Clare’s sat, cast a long shadow on the little red brick school.

And Cedric knew that he should want to go to McCleiss. If he was ambitious enough he would go. He never understood other people his age or older who tended to deny their age, who didn’t want to admit that yes, at twenty-four, five, six and above, they probably should have been out of school a long time ago. They were not as young as the others. Some people were good at shouting down invisible name callers. Shirley, who would probably be valedictorian, was approaching thirty, and one day Cedric had heard her shouting at a vending machine, “I’m NOT that old.”

But Cedric knew that he was that old, and for all the world could not see getting excited about going to get his Masters or anything else at McCleiss. College had been good to him. It had been really good. But he had to move on now.

Where on was he could not say.

Graduation came. Evelyn was there. Gladys was there. Ida came. Ralph did not. Almost thirty years later, Cedric remembered Louise, ten years old standing before him, looking horrible, say, “Mama thought you’d never gradu—ouch!”

And then Gladys hissing, “Louise!”

His grandmother had been present as well, but if Estelle had done anything, said anything or was even in the position to say anything given her advanced years, Cedric could no longer remember.

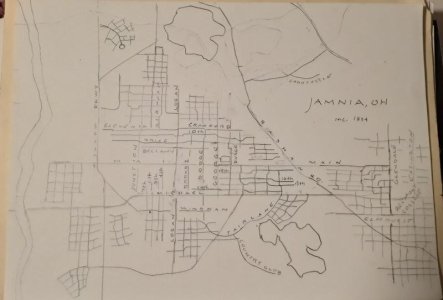

He did remember the days after graduation, sitting up in bum-fucking-Jamnia, which seemed more like nothing than it ever had before, smoking cigarettes and watching all his opportunities dry up and flake away like roses, and Cedric certainly didn’t want anything that came his way.

He played a lot of poker with Cousin Letmee, who wanted to know what had happened to the gun. This made Cedric think of Marilyn, and this only made him sadder. He never slept past eight o’clock. It would have just been giving into despair, and he still dressed well, and went to daily Mass though Mass was starting to be a strain since he was having a hard time believing in anything.

In the middle of that incredibly stifling summer, they got a new priest. James Brumbaugh had said little except that he had been born in New York, and came from Holy Spirit monastery up the hill.

Surely this time in his life must have been more insufferable than he remembered. After all, he was only twenty-four, and could compare it to none of his future tragedies. And then, at the time, he did not have the comfort of knowing that time really does make one forget, compact those things that seem so long. So it must have been horrible at twenty-four to be this depressed.

“It could be so much worse,” he told Ida when he was finally willing to tell anyone how he was feeling. “I could be in Viet Nam.”

But this only made him feel worse because he felt guilty for not feeling as bad as the men coming home from Viet Nam.

The last thing Estelle did was walk into the living room of Evelyn’s apartment where Cedric was finishing the last of a pack of cigarettes.

“Look at him,” his grandmother complained.

“God, Estelle. He’s getting his life together.”

“Doesn’t look like he’s getting his life together. Looks like he’ll turn into another DuFresne, Sandavaul drunk. Looks like he’ll be just like his father.”

“Looks like you should shut your mouth, Estelle,” Evelyn said.

“That’s what comes of bringing bastards into the world,” Estelle concluded.

Cedric stood up, a little unsteady from the liquor, and looked at his grandmother. He said something that had started out, “Now, look you old bitch- ”

And where it had ended, no one could say.

Estelle had, somewhere in the midst of her grandson’s tirade, clutched her chest, and fallen to the ground. When Evelyn went to her knees to check her sister’s breathing, she looked up at her nephew and said, without any note of accusation, “Well, damn, Ced. You killed her.”

At the funeral the news soon went about first through Estelle’s children, and then her other grandchildren as well as Evelyn’s wayward brood, that Cedric had killed Estelle with a word. No one accused him. Everyone seemed to revere him a little. Gladys told him he could probably sit around on 1133 Crawford writing stories and plays for the rest of his life, and never work. In families that large a patriarch just had to be there, and Cedric had certainly made himself patriarch. There were few women as proud of their sons for murdering their mothers as Gladys DuFresne was of Cedric.

But Cedric did not settle down to write in the back of 1133. He did not want to write or act. He wanted to get a new life. So the day after the funeral he loaded up a Samsonite suitcase, and without warning, caught a cross-town bus that shot out to Holy Spirit Monastery.

Julian Brown had not been ordained long, and he still had hair when he answered the door. In 1974 one did not knock and enter into a hall. Instead there was a cord outside, and when the visitor- this time around Cedric- pulled on it, a great boom came from the inside, and then a monk would come to answer the door.

“I’m here for privacy and thought,” Cedric said. “I just can’t be bothered with questions. I came to put my life together... Or take it apart. I don’t know which.”

Julian, to his credit, smiled and said, “Come right on in.”

“I’m sure we have a spare room somewhere around here,” Julian was telling Cedric. He led him upstairs, and they began the long hunt around the rectangular monastery while Julian gave a history of the house, of the Poor Clares who had come long ago, but not remained. And Cedric told of how his school had once been part of a Poor Clare convent.

“She’s all over the place isn’t she?” Julian said.

When Cedric cocked his head, Julian explained, “Clare.

“Ah,” Julian jiggled a doorknob, opened it. It smelled musty. “Here is a spare room. I’ll let the abbot know you’re here.”

Marion was abbot then. He was already impossibly old, and he made no sound when he walked, so Cedric nearly hit the ceiling at seeing the ancient monk appear in his room.

“We’ve been expecting you,” the abbot said cryptically.

“Really?” said Cedric.

Then the monk threw back his head and laughed.

“Of course not, but didn’t it sound ethereal?” He waved his fingers around.

It was not hard to talk to Dom Marion, and it was later that evening that he found himself telling the man, “So the last straw was: I killed my grandmother.”

Dom Marion looked at Cedric quizzically.

“I shouted at her, and she dropped dead.”

A great gush of air came out of Dom Marion, so great that Cedric feared that he might have killed him as well. And then the old abbot said, “You must feel terrible about that.”

“I ought to,” Cedric said, “Only, she did have it coming.”

Julian and Mario were in their thirties, but they explained to Cedric, “Monasticism has a way of keeping you younger.” So the three of them had a ball in the most monastic sense of the word. Holy Spirit was outside of Jamnia City Limits. It was like being in a different world. Things went on peaceably. No one asking Cedric if he would join the community or not.

One day Brother Crysoganus told Cedric, “We have a visitor. From New York. Staying in the old nun’s room.”

Everyone was curious, but with the curiosity of monks, so not a word was mentioned about the new visitor. And no one saw him. Cedric was preoccupied with the matter of prayer. He spent a great deal of his free time before the Blessed Sacrament, first asking God for what he wanted, and then asking God to tell him what He wanted, and then asking God to just do whatever was supposed to be done.

Julian came looking for him, and the two of them were heading toward the lake by way of the chapel’s back exit.

“I don’t know, Julian,” Cedric told his friend. “It’s like I say, God, give me patience- ”

“But give it to me right now!”

“Exactly!” Cedric laughed looking up at the vaulted ceiling and clutching the air theatrically.

“I don’t know what I expect,” he shook his head. “I suppose I want God to drop his will down from the sky onto my head!”

And then there was a groaning, a tearing, a shower of dust and a scream when a woman fell through the roof, through the chapel, and crushed Cedric beneath her.

He groaned on the chapel floor while Julian looked up at the hole in the roof, and then the woman looked down at him and smiled while Cedric muttered, “Marilyn Alexander, what the hell are you doing here?”

“Well, I was working Atlanta,” Marilyn explained between mouthfuls of food, “Ever been?”

“No.”

“Don’t,” she said. “Too damned hot. And what’s more, nothing but drag queens. Most depressing part? Some of them looked better than me.”

Marilyn finished her water. They were in the dining hall of the monastery, and Julian had said Marilyn was the first woman to ever sit here.

“So I swallowed my pride, and went to New York.”

“New York’s nice,” Mario said.

“Not if your father lives there,” Marilyn told the monk. “And he’s the lousiest son of a bitch I ever met. Scuse the language.”

“You can say lousy whenever you want,” Mario excused her with a grin.

“I was doing this show I really didn’t want to do, Ced. Feeling all useless and everything. Sometimes I would look at the gun you gave me, and just smile.”

“Gun?” Julian raised an eyebrow.

“Long story,” Cedric and Marilyn both said.

Julian shrugged.

“I needed to find you,” Marilyn said. “You were unlisted at Saint Clare’s. And then when I finally found out where you were- ”

“I was staying in a boarding house.”

“I know that now,” said Marilyn. “You were never home.”

“I never got the message.”

“I should strangle that woman,” Marilyn said. “But anyway, after a while, I figured you had to be graduated. So then I had to start trying to remember where you lived. Then I had to dig up Saint Clare’s records.”

“How?”

“Oh, I drove to Ohio.”

“Really?”

“Really, Cedric.”

“Just for me,” Cedric murmured, feeling a little pleased.

“And for my sanity,” Marilyn told him. “I thought I might lose my mind if I didn’t find you. Can’t explain it. Just thought that it might happen that way. So I finally found out you were here... in Jamnia. Which I remembered the town name once I saw it in print. But you know, it’s sort of a hard place to remember. And then I called up all over town and found out you were here.”

“So you chose to fall on my head?”

“No, no,” Marilyn shook her head rapidly. “Having come here I had to decide why it was so pressing for me to find you or find anyone. I had to get my life together, you see? Reflect. Think. So I came here for that. I just reflect best out in the sun, and the sky was so beautiful today. It really is Cedric. We should take a walk. I was going along the roof tiles.”

“Why the roof tiles?” Mario asked Marilyn.

“Because no one can see you on the roof,” she explained. “With the little parapet and all. Real private, you know? So I was going along them when I fell through it... Onto you.”

“Now that,” Julian commented, “is romance.”

“See, I can’t believe you guys never tried this,” Marilyn told them, walking along the parapet. They looked over the parapet and onto the deep green of the trees, the blue of Lake Clare, and the clearer, pearl blue of the sky and its clouds. In the distance the city was small. Nearly invisible.

“I feel sorry for anyone who couldn’t feel at home in the world on a day like this,” Marilyn said, clasping her hands. “It’s a good world. That the Lord made.”

“You and Cedric could stay with us forever,” Dom Marion suggested. “and keep us all young.” He pointed to Mario and Julian, then amended, “younger.”

“What a joke,” Marilyn murmured.

Dom Marion gave a hooked grin, and said, “You thought I was joking?”

They rounded the whole of the parapet, taking in the fields to the northwest nearly ready for harvest, and then the long slope veiled in trees which overlooked the highway.

“Oh my,” said Marilyn, excitedly grabbing Cedric’s wrist.

“Hum?”

She pointed below to where the road from the highway emerged from the green trees. Someone who appeared to be—from the size of his Afro—Jimi Hendrix was coming up to the monastery. No, he was a little too light complexioned for Jimi. Besides, Jimi was dead.

Cedric stood, scrutinizing the fellow who was about to pull the cord of the main door, and then, suddenly, he called out, “You cheap son of a bitch!”

And taking off his shoe, Cedric Fitzgerald launched it at Ralph Hanley’s head and knocked him cold.

“Well, now we’re all together,” Abbot Marion said cheerfully, clapping his hands as Ralph stirred from sleep.

“Cedric, one day you will explain to me why you did that,” Marilyn told him.

“How do you know him?” Cedric demanded.

“Ralph is the one who told me you were here.”

Ralph, with a considerable dark lump over his right eye, was looking at both of them.

“What’s going on?” Ralph said.

“What’s going on is I’m considering giving you another knot on your head, nig- ”

“Cedric,” Marilyn warned.

Cedric shut his mouth and fumed.

“Was it you?” Ralph said, “who threw that thing at my head?”

“It wasn’t a thing. It was a Florsheim. I paid thirty-eight dollars for those.”

Cedric lifted his foot, and began to polish the shoe with which he’d hit Ralph.

Ralph opened his mouth.

“And before you ask me why I did it,” Cedric beat him to the punch, “I’ll tell you it’s for missing my graduation, adopting a holier than thou attitude when you decided to be a priest and not bothering to call or show your face since I’ve been back in Jamnia. And not necessarily in that order.”

Ralph sat up, and looked at Cedric, his green eyes sharp bottle chips.

Not giving a damn, Cedric continued: “Not to mention the completely bitchy attitude you took when I came to Sainte Terre, the prompt decision to go out of your way not to attend Saint Clare’s with me—not that you had to. Obviously you didn’t have to. And about a million other things I can’t think of right now.”

“I brought Marilyn to you,” Ralph said.

“Well now that’s the one good thing you did do.”

Ralph sighed, and laid back down on the cot, placing a hand over his bruise before wincing at the pressure of said hand.

“Can we start all over again?” Ralph demanded.

“Hell no- ” Cedric began.

But Marilyn cuffed him in the head. There was such a look in her eyes that Cedric, sulking, said, “Okay... But just for her sake.”

Ralph put out a hand, cocked his head in Cedric’s direction, and stuck it out.

“I’m Ralph Hanley.”

“I’m Cedric Fitzgerald,” said Cedric.

“See how new that was?” Ralph said. “The first time we met, you didn’t even have the same name.”

“What?” said Marilyn.

“It’s a long story,” Cedric explained.

The three Black people, and the three black monks sat around in the infirmary for a few moments longer, and then Abbot Marion clapped his hands together again in his brisk manner, and turning to Marilyn and Cedric said, “So when will you kids be getting married?”

GEORGE STEARNE HAD ALWAYS BELIEVED that eventually everything had to be paid for. He still believed it. Only what now was taking shape in his mind was the idea that maybe all the payments might not be as cruel as he was previously certain they would be.

As he searched for his jacket- wondering if he’d even need one, and then deciding he would- George admitted that he had been embarrassed, was still embarrassed about Ashley. The odd thing was that he wanted to talk to Tina about it. He vowed that one day in the future, when the six years age difference didn’t matter, and it wasn’t a student-teacher thing, he would talk to Tina as a friend. She was younger, yes, but George recalled seeing Kevin Foster’s mother-in-law and Cedric Fitzgerald together. There was certainly an age gap between Ida Lawry and Cedric, yet they were the best of friends.

There was a knock on the door. George wondered if it was the forceful Tina, and the thought made him grin. She was a hell of a person, and when she realized that one day…

“Watch out world,” George was saying as he opened the door, and prepared to zip his jacket.

“You fucked her!” was what Mick Rafferty said as he walked through the door.

For a moment George was confused.

“You fucked her. Didn’t you, George?” Mick demanded. “That was why you were always shaking your finger, and disapproving, and warning me. You’d been with her a long time ago.”

George sucked in his breath, then sighed and said, “Mick, in case you didn’t notice, everyone’s been with Ashley Foster a long time ago.”

Mick stood before his friend, silent. He shoved his hands in his pockets, and then said, “Why didn’t you tell me?”

“You didn’t tell me,” George said.

Mick didn’t respond to that. He just looked out of the sliding patio door, the little lake glinted darkly in the evening, almost invisible.

“I am so fucking embarrassed,” Mick said.

“That would make two of us,” said Stearne. “I tried to tell you.... without telling you.”

There was nothing to be said. Stearne took his hands through his black hair, and then said, “Hey, listen. Tina invited me... and you too... out with her and Luke and I think Madeleine Fitzgerald. I gave in and said yes. Graduation’s not that far off. I’ll buy ‘em a round of drinks, and lose to Tina at pool.”

“Is she that good?”

Stearne nodded and said, “It’s the only thing she inherited from Colonel Foster. Why don’t you come along?” When Mick didn’t answer, Stearne said, “Alright? Com’ on, Mick.”

Mick Rafferty blew out his cheeks and said, “Well, I don’t want to be alone tonight.”

“That’s the spirit,” Stearne said. “Kind of.”

MORE TOMORROW